“Danger, Will Robinson!”

Irwin Allen made his departure from the cinema to the small screen when he developed his concept for a space-based series called Lost in Space. Financially backed by comedian Red Skelton, the idea was quickly embraced by James Aubrey who secured the series for CBS. Concurrently, producer Gene Roddenberry was pitching his own space-based adventure and exploration series called Star Trek. Aubrey flatly rejected Roddenberry saying that Lost in Space had far more commercial appeal and would bring a longer lasting audience.

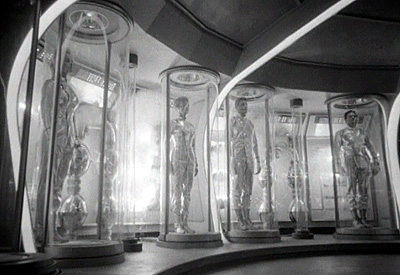

The 1964 pilot was based on a script by Shimon Wincelberg and enjoyed a budget of $600,000 which made it the most expensive pilot episode ever produced until that time. It told the story of the launch of Gemini 12 on 16 Oct 1997, a vehicle that was to take the world’s first space family to colonize a planet in the Alpha Centauri star system. Led by Professor John Robinson (Guy Williams), the family consisted of his wife, Maureen (June Lockhart) and their children, Judy (Marta Kristen), Penny (Angela Cartwright), and Will (Billy Mumy). Accompanying them was Major Don West (Mark Goddard) who served as the vehicle’s pilot. The flight plan called for this crew to be placed into suspended animation for a 98-year journey.

As filming began, Allen, an avid supporter of the U.S. space program, invited Chris Craft and other NASA officials to assist the production crew. At the time, NASA was looking for ways to promote the space program and welcomed the opportunity to influence Allen’s space opera and excite viewers over the prospects real-life space exploration. NASA representatives quickly realized that Irwin Allen wasn’t interested with actual science or technical flaws. Technical advisor Chris Craft informed Allen that the design of the spaceship would never fly as it had serious aerodynamic problems. Allen responded that a hundred years ago men were saying the same things about the rockets NASA was sending into space. The two-foot spaceship miniature moved on wires and that provided all of the science Irwin Allen needed for his series. NASA abandoned the production and embraced Roddenberry’s attempt, integrating science into the scripts whenever they could.

When the pilot film was completed, Irwin Allen widely announced that it was beyond doubt his “best work ever”. The CBS executive staff didn’t agree. A few openly laughed at the film causing Allen to go into a rage and stop the film midway. Allen was ready to use whatever leverage he had to stop all series production when story editor Anthony Wilson pulled him aside for a private conversation and explained that although some of them laughed, everyone in the screening room loved the show. Irwin Allen stepped away from the project momentarily as Wilson went to work.

Wilson coordinated with studio executives to determine why the pilot had drawn the wrong reactions. They determined a number of causes, including a belief that the final pilot was too “hardware-driven” and relied too heavily on special effects. Wilson decided that the series needed an element to pull things together and determined that they needed a recurring villain to create conflict and liven the story. Irwin Allen loved the idea and declared that he wanted someone similar to Flash Gordon’s Ming the Merciless. Wilson had sketched out a Long John Silver character instead. They reworked the concept eventually devising a new character named Dr. Zachary Smith.

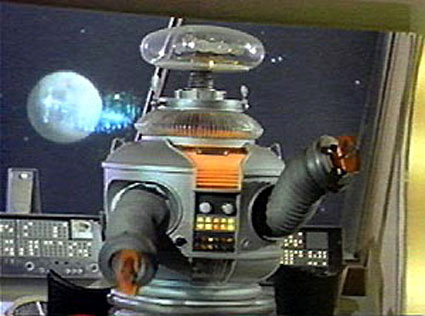

Smith was developed to be an agent for a hostile foreign nation that was caught aboard the spacecraft in his attempt to sabotage it just prior to its launch. His actions fail to prevent the launch but do cause the ship to veer off course and crash-land on a far away desert planet. Actor Carroll O’ Connor was seriously considered for the role before he was replaced by the very talented Jonathan Harris. To round out Smith’s introduction, Wilson also added an environmental robot, Robot YM-3, designed by Robby the Robot designer, Robert Kinoshita. With the assistance of this mechanical ally, Smith was ready to continue to confront the Robinsons.

Concurrently, Irwin Allen took the opportunity to rename the Gemini 12 spacecraft. Now called the Jupiter 2, it marked the final separation between Allen’s production and the NASA advisors they had once hoped to court.

The depth of the changes meant that the 1964 pilot couldn’t serve as a pilot for the series. Most of the footage was edited and used to flesh out the first five series episodes. The series budget was limited to $130,000, fairly modest compared to the expected weekly budget. Since the Jupiter 2 standing sets formed the basis of the show, the budget proved to be adequate. Studio executives warned that, since the Jupiter 2 had cost $350,000, Lost in Space had to run successfully for at least three years to be considered a financial success.

On 15 Sep 1965, the series premiered to widespread critical acclaim which did little to impress the Studio executives who declared that if Lost in Space didn’t have at least a Nielsen rating share of 20 or higher, they would declare the idea a failure. The premiere scored a rating of 18 and slipped the following week to a rating of 17.6 with a further slip the next week to 16.9.

CBS Chairman William S. Paley was enraged at the poor results. Already skeptical of the project, he considered Lost in Space to be an embarrassment for a network he considered to be the leader in quality entertainment. He issued an edict that if Lost in Space didn’t deliver a strong audience in a few episodes, it was to be immediately halted so the studio space could be devoted to a more worthwhile series.

In the same week, letters began to pour into the studio mail room. One, a formal request from a technical department of the US Air Force wanted to know if the robot was a real machine or if there was a man inside. Irwin Allen personally responded and explained that the robot was controlled by Bob May and the robot’s voice was provided by announcer Dick Tufeld, the same man who provided the show’s suspenseful narration.

However, the core of the letters concerned Dr. Smith. Most of the viewers loved him, even though he was a cunning, cruel, evil man with only two motivations, namely to kill the Robinsons and return alive to Earth. In the first couple of episodes he’d already sabotaged the spacecraft, damaged Professor Robinson’s parajet pack, and ordered the Robot to “liquidate” the family members one by one. Anthony Wilson and Jonathan Harris decided to refine the character, believing that such pure evil wasn’t going to last with viewers throughout the season. With careful planning, Harris softened the character to transform the murderous spy into a cowardly and lazy lingering problem.

Dr. Smith began comical exchanges with the robot, referred to only as “Robot”, and caused problems for the Robinsons through ignorance and bumbling stunts rather than maliciousness. The Robinsons proved remarkably forgiving for his mistakes. When he used the last of the spacecraft’s drinking water to enjoy a shower or traded Will to brain-snatching aliens to protect his own well-being, they merely corrected their latest problem and energized their latest attempts to return to Earth.

As the series progressed two themes developed. Professor Robinson attempted to turn Smith into a useful space pioneer by giving him simple tasks like digging wells and standing guard. Smith always ignored these responsibilities, expecting Will or the Robot to accomplish the work. This enhanced Smith’s new reputation as a greedy, pompous, and inept tag-along. Balancing this tolerance was Major West who rightly saw Smith as a serious threat to the team’s survival.

The changes worked well. By the sixth episode Lost in Space had surpassed a Nielsen rating of 23 and was increasing in popularity. The show quickly built a steady fan following. Irwin Allen happily announced that the show was a hit. The success confounded William Paley who hired a psychologist to observe the Lost in Space production and research its viewership to discover the mystery of its appeal. Paley was convinced that the show was being watched by people with defects. The psychologist determined that the show’s viewers were relatively free of any mental flaws and that the only flaws existed in the shows shoddy science.

Paley was dissatisfied with the report and hired the highly respected chairman of Rutgers University, George Horsley, to conduct the same study. Horsley’s evaluation explained that the appeal was based in the fact that the show portrayed a family working together in harmony and demonstrated positive human values. It also demonstrated that advanced technology would serve mankind, not enslave it. Most importantly, the show portrayed heroic characters with good moral values.

For Anthony Wilson, these studies were important but they totally missed the mark. He knew that viewers tuned in because Lost in Space delivered adventure and challenges in exotic settings and clever situations. Whether the latest episode showed Will blasting a towering Cyclops with a laser weapon, Penny posing as space royalty to serve as a negotiator between warring alien factions, or Professor Robinson fighting possession by evil alien spirits, the series continued to throw one thrill after another. The Robinsons couldn’t as much as have a peaceful dinner in the campsite outside their spacecraft without being interrupted by cosmic storms, space wizards, or wandering monsters.

More often than not, those monsters were played by Dawson Palmer who dressed in various creature costumes to threaten different members of the Robinson family. Donning costumes with poor visibility he reacted to abusive stage direction with relative good cheer, often shouting profanity as he swung his arms or made soon-to-be-edited out grunting noises.

As the series popularity increased, the show experienced increased scrutiny from the network’s censors who expressed ever-growing concerns about the impact it might be having on its audience’s younger members. They constantly sent the production team reminders warning them to “use appropriate judgment”. These mandates became more and more frequent until the team felt they were straight-jacketed. The restrictions increased until such offensive aspects as on screen kissing between Professor Robinson and his wife Maureen had to be eliminated because censors felt it would disturb younger viewers and embarrass older ones. After campaigning by Irwin Allen through senior CBS executives, the husband and wife team were allowed to show affection through “hugs, pats on the arm, and affectionate looks”.

By the end of the first season, Jonathan Harris received far more fan mail than all the other cast members combined. Letters to the studio clearly showed that he was the most popular character of all. This caused the writers to completely abandon the show’s survival storyline and focus almost exclusively on Smith, Will, and the Robot. The refocusing angered Guy Williams who was accustomed to being the star and didn’t like being upstaged. He demanded the same treatment he’d earned when he was the lead in the Zorro TV series. He opposed his diminished role and demanded that the refocusing efforts be stopped.

Irwin Allen responded by threatening to write Williams off the show entirely. Lost in Space had found huge success and was crushing competing programs in the ratings, including the formerly indestructible Ozzie and Harriet Show, which only a year before was thought to be unmatchable in ratings. Lost in Space not only matched it – but surpassed it by a mile!

The second season gained the benefit of being broadcast in color. This caused further concern for network censors who warned that monsters in color were far more frightening than their black and white counterparts. They also began to hack at small elements of dialog throughout the show, forbidding the use of the word “kill” and insisting it be replaced with the words “destroy” or “disable”.

Irwin Allen showed little concern for the censors and became less focused on the specific hassles of the production as the Lost in Space franchise exploded. Merchandise soared to an all-time high. Lost in Space sketchbooks, Viewmaster slides, robot toys, games, and Aurora plastic models all sold in record numbers making Allen a strong heavyweight throughout Hollywood. Ironically, despite the strong sales of all things related to the series, Aurora refused to issue a Jupiter 2 model, claiming that a flying saucer model was just too boring to sell.

The series also faced a growing challenge in the battle for dominance in science fiction on TV from Star Trek on NBC. Although Lost in Space overpowered Roddenberry’s series, Star Trek’s contrary view of space adventure was gaining attention. Critics liked the more adult treatment of the genre and respected that Rodenberry had gained the support of some accomplished science fiction authors. Conversely, Dr. Smith, now the center of the Lost in Space, became ever more comical and bumbling as he confronted space Vikings, gunslingers, lost knights, and wildly dressed magicians. While Smith, Will, and the Robot stumbled through one situation after another, the rest of the Robinsons were left picking up after them. By the middle of the second year, some episodes didn’t feature Professor Robinson or Maureen at all. Given the conditions on the set, the actors displayed winning personalities in the face of some very frustrating working conditions.

By 1967, they were growing weary of the situation as was most of the audience and Dr. Smith’s charm began to wear thin on some of the viewership. Despite Jonathan Harris’ strong talents, viewers found Smith’s character tiresome. Older viewers were leaving the show in large numbers and in the second half of the season, Lost in Space slipped from the Top 20 to competing for the 44th position on the Nielsen list.

Behind the scenes, the series had another serious challenge. Anthony Wilson had been hired by ABC to work on The Invaders. Still a supporter of Lost in Space, he contacted Irwin Allen and suggested that they drop the whimsy aspect of Smith for the third season and return to a more pure action-adventure format that leaned closer to Star Trek’s theme of setting the characters against strange environments and more credible threats. He also prompted Allen to enhance the focus on hardware, always a favorite with audiences of the time.

Allen arranged for more dynamic shots of the Jupiter 2 to be filmed and introduced the Space Pod, a landing craft that dropped from the spacecraft’s bay doors. He also hired composer John Williams to enhance the show with dramatic new music. The scripts shifted focus to highlight a different cast member each week, providing each character a chance to develop through more versatile stories.

The changes seemed to work and by the end of the third season Lost in Space was again on a ratings upswing. It wasn’t enough. CBS executives cancelled the series. Irwin Allen and the rest of the production team was informed of the cancellation only when a blanket notice was sent from the executive offices to the entire staff. He was outraged and immediately began to rally fans and supporters in the media to support a call to continue the series. The effort failed miserably. The core of the Lost in Space fanbase was still older children and young adults who could do little to influence the thinking of major studios. CBS executive Perr Lafferty allowed Allen one chance to detail how a fourth season would develop and instructed him to provide detailed story outlines. Instead, Irwin Allen arrived, talked about the show’s past strengths, and promised the next season would be the “best year ever”. The executives were not impressed. They confirmed the cancellation.

The Robinsons adventure had come to an end.

– written by Russell Sanders