Science fiction was a popular subject in the earliest days of filmmaking. The works of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, among others, found their way onto the new medium of celluloid in movies that were typically just a few minutes in length. George Melies’ 1902 Voyage de la Lune (Trip to the Moon) is among the most influential and famous of these (see our article on this seminal sci-fi movie here).

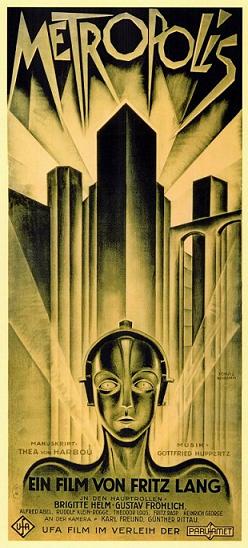

In 1927, German Expressionist Fritz Lang took this film genre, and filmmaking in general, another important step by creating his spectacular, Metropolis. At the time the most expensive film ever made (reportedly 4 Million Reichmarks, approx. US$950,000 in 1925 dollars), Metropolis ran approximately 153 minutes (about 2.5 hours).

Set in the year 2026, Metropolis portrayed a dystopian society ruled by intellectuals from their high towers, supported by the workers in the city below.

|  |

The story centers around the son of the city’s creator and ultimate leader, Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), who is enjoying a pleasure garden when he encounters the lovely worker maid Maria (17-year old Brigitte Helm in her first film role), who is showing a group of worker children how the elite live. Although she is immediately chased from the garden, the naive Freder is fascinated by the girl and follows her into the city’s depths, where he encounters the hardships the workers are forced to endure. When he reports what he’s found, his father is not unmoved, but other players have a hand in bringing tensions between the two groups to a boiling point, and there is much death and destruction before Freder is able to defuse the situation, with the help of the lovely Maria, one of the worker bosses, and his father.

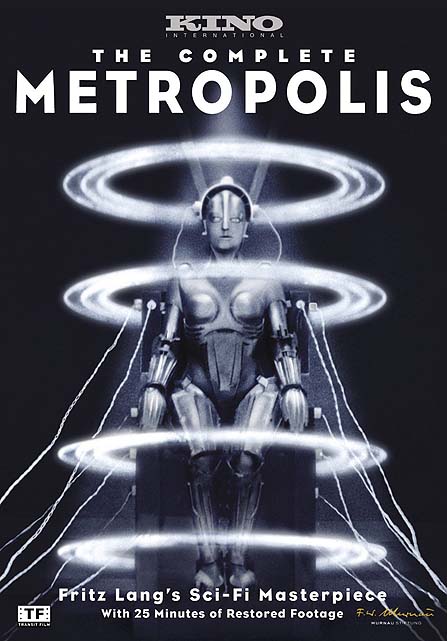

And this description does not do the story any justice. It is an involved if not overly complex story, complete with a mad scientist, spies, spectacular special effects, and an autonomous robot, which may be the one iconic image that came from the film that is recognizable to this day.

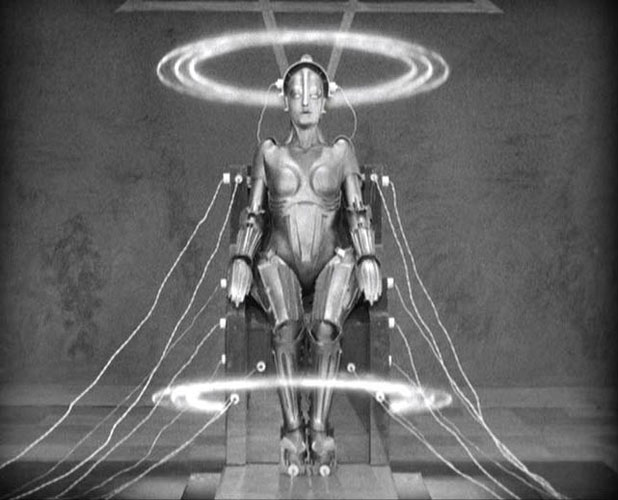

“Rotwang,” as portrayed by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, is a brilliant scientist driven insane by his unrequited love for Hel, the late wife of the city’s founder. He is hard at work creating a robot with the intent to “resurrect” his dead love, much to the horror of her widowed husband, when he encounters Maria – who he proceeds to kidnap and he creates the robot in her image. Unfortunately for all concerned, the “false Maria” becomes responsible for goading the workers to war, forcing the real Maria into hiding; the robot is ultimately exposed and destroyed, and an era of mutual understanding between the thinkers and the workers is obtained.

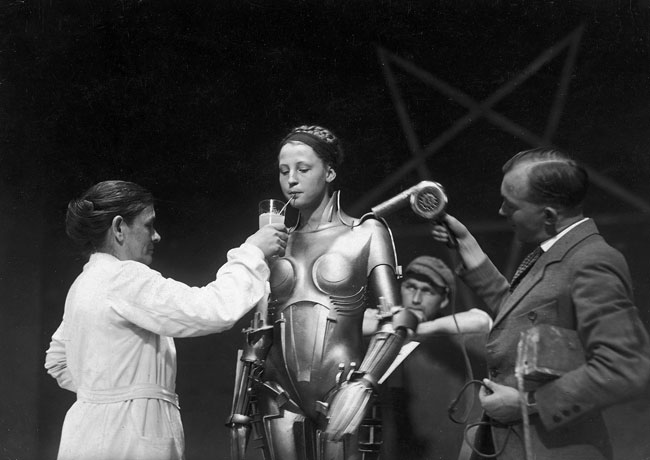

The special effects surrounding the making of the robot (and its destruction) were beyond state-of-the-art for the time. Indeed, new techniques were developed for this film. Without the benefits of digital animation, each shot had to be made with real people, real costuming, real props, real fire. It was an accident of providence that as the robot was being designed the designer, sculptor Walter Shultze-Mittendorf, found a sample of “plastic wood” (a pliable material used as wood filler) which gave him the perfect material to create the costume. A whole-body plaster cast was taken of Brigitte Helm (who played both Maria and her robot doppelganger) and over it Shultze-Mittendorf built the robot suit. Once cured and finished, the costume was sprayed with a paint that gave it a metallic look.

The costume was so restrictive that Ms. Helm suffered numerous cuts and bruises during the filming, and at one point passed out because she was unable to breathe properly.

Other special effects, created by master Eugen Schüfftan, included what became known as the “Schüfftan Process,” the use of mirrors to make it appear the actors were occupying miniature sets (much of the city was actually done in miniature). Alfred Hitchcock would use this method in his 1929 film Blackmail.

From the moment filming began in 1925, Lang pushed the cast and crew to the limit in order to get exactly the shots he wanted. Days were spent in cold water to depict the flooding of the city, demanding multiple re-shoots of scenes, and the actors (and extras) were pushed to the point of illness and exhaustion. Filming took over a year to complete.

The movie opened to mixed reviews; despite its historical significance and ultimate place on the list of all-time-best silent movies, not many critics of the time were impressed. H.G. Wells, in an extensive pan published in the New York Times called Metropolis “…quite the silliest film.”

Nazi propagandist Josef Goebbels, however, loved the film and the message he took from it. In fact, Thea Von Harbou, then Lang’s wife and co-writer of the film, would enthusiastically join the Nazi Party in 1932. Lang divorced her in 1933.

Lang would later express his great disappointment in the film (perhaps in part because the Nazis found it so fascinating) in an interview with filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich (“Who The Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors” published by Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), saying he found the finished product “silly and stupid.”

Sadly, after the German premier, scissors came out and the film was dramatically shorted. Ostensibly due to it’s long running time, playwright Channing Pollock was commissioned to shorten the film. Reference to the character “Hel” was removed (which took out the major motivation for the story), because of the similarity between the name and the English word “Hell,” which at the time was considered inappropriate. The more overt “Communist” ideology of the film was deliberately muted, as well (the Communist philosophy presented in the film was, according to Lang, the work of his co-writer; not being politically-minded at the time, his own interest was in the machines and the imagery). In all, almost 40 minutes of the film was excised, and much of that material was believed lost forever.

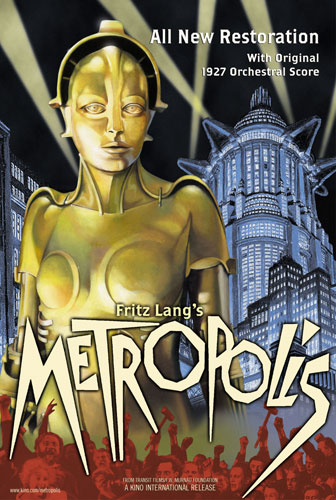

However, over the years preservationists found prints of the film in the possession of several collectors and museum vaults that have allowed them to piece together most of the original film. In the 1980’s, an 80-minute version of Metropolis was released by Giorgio Moroder with a pop-music soundtrack performed by the likes of Freddy Mercury, Pat Benetar, and Adam Ant. Spurred by the success of the Moroder version, Enno Patalas began the exhaustive process of finding and reassembling as much of the original film as could be found, and released another version of the film in 1986. Still another restored version, with the original soundtrack as composed by Gottfried Huppertz, was released in 2002.

Then in 2005 and again in 2008 heretofore unknown prints of the film were uncovered in New Zealand and Argentina. In poor condition, they required extensive restoration before they could be used to restore the original film. These prints, apparently from the destroyed original 35mm masters, were invaluable to the restorers who finally had a resource that not only supplied missing footage, but also told them which previously cut scenes went where; up to that time they had to make educated guesses in how the film was originally edited. In February of 2010 the fully-restored Metropolis premiered simultaneously in Berlin and Frankfurt.

This film was also plagued by copyright issues that were ultimately decided by the US Supreme Court. The US copyright had expired in 1953, putting Metropolis in the public domain, which saw a number of versions of the movie released. But in 1998 the copyright was extended by court order, prompting some of those who thought it should remain in the public domain to appeal. In January of 2012 the Supreme Court upheld the copyright extension and the film is now copyrighted through 2023.

The Tombs of Kobol would like to thank Kino International (the current copyright holder, http://www.kino.com/metropolis/) and the Internet Movie Database (http://www.imdb.com) for invaluable data in compiling this article. Many of the images on this page came from Kino’s website, and we are indebted to them for their use.

Metropolis is available on DVD and Blu-Ray from Kino International (http://www.kino.com/video.php?id=1162). It is also available through Amazon.com and other retailers.

Also, my personal thanks to our old friend Jaeson Jrakman, who found the following wonderful articles about the making and restoration of this important film, which were also instrumental in the preparation of this article:

A piece written by sculptor Walter Shultze-Mittendorf himself about the making of the robot, from Cinefantastique magazine: http://cinefantastiqueonline.com/2010/05/the-making-of-metropolis-creating-the-female-robot/

The biography of Herr Schultze-Mittendorf: http://www.cyranos.ch/smmitt-e.htm

And from wired.com, a fascinating bit of history, including one of the original film programs from the premier: http://www.wired.com/underwire/2012/07/rare-metropolis-film-program-from-1927-unearthed/

Written by John Pickard