“My God, it’s full of stars!”

In 1982, Arthur C. Clarke (who never writes sequels) published the sequel novel to 2001: A Space Odyssey, 2010: Odyssey Two. Two years later (1984), the novel was released as a film, 2010: The Year We Make Contact. Peter Hyams (Capricorn One, Outland) wrote, produced and directed the film which flaunted two Hollywood heavyweights, Roy Scheider and John Lithgow, strongly supported by Helen Mirrin and Bob Balaban. Hyams successfully negotiated for Douglas Rain to return as the voice of the HAL 9000, an addition that gave strong support to this sequel to the grand classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The film opens with a sequence of stills from 2001 with computerized text printed across the screen. These explain the main events of the first film, representing excerpts from a report filed with the National Council of Astronautics by Dr. Heywood Floyd, the man ultimately held responsible for the failure of the Discovery’s mission. After the failure of Discovery, Floyd was drummed out of the chairmanship of that council.

It is now 2010. Dr. Floyd is now a university Chancellor visiting an antenna field on the high desert. He is visited by Soviet big shot and old friend Dimitri Moisevitch who reveals that the Soviets have finally accessed Dr. Floyd’s classified report and are building a ship to make the journey to Jupiter. The U.S. government is building the Discovery II – but the Soviet ship will be ready far sooner, and will reach Jupiter a full year before the Discovery II can make the trip. The original Discovery, and the ‘lobotomized’ HAL, will be in the hands of the Soviets long before the Americans, and there is nothing the Americans can do about it. Tensions between the US and Soviet governments have drastically increased over the past few month over a conflict in South America and rumors of war are becoming more prevalent.

Yet, Dimitri is a brilliant man who is disinterested in national conflicts. He recognizes the value of the Americans and Soviets working together. The Soviets need Dr. Floyd to access HAL and gain the vital information that caused the catastrophic failure of its mission. Dimitri fears that without that knowledge, whatever happened to the Discovery could happen to the Soviet mission. As it turns out, the US needs the Soviets even more badly. Something has disturbed the orbit of the Discovery and it will crash into Io long before the Discovery II could arrive.

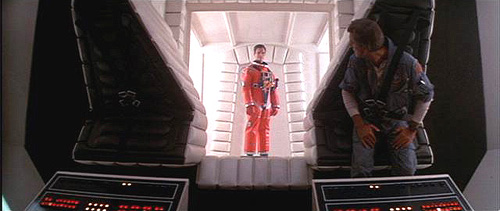

After some political wrangling, three hibernating Americans are placed aboard the Alexei Leonov when the ship departs for Jupiter. Dr. Heywood Floyd (who leaves his second wife and young son to make the long, dangerous journey), Dr. Walter Curnow (who had until that time been in charge of building the Discovery II, thought to have the best chance of entering and reactivating the Discovery), and Dr. R. Chandra (HAL’s inventor and the person thought to have the best chance of determining what had happened to HAL on the original mission) compose the American team. Dr. Floyd’s participation in the mission is one of personal retribution: six people sent on a mission he designed died mysteriously. He feels he owes it to them to find out himself what had happened as well as discovering the meaning of Bowman’s final transmission, sent from the space pod before all contact was lost: “My God – it’s full of stars.”

The Alexi Leonov is launched with orders to awaken the Americans when the ship reaches Io unless something unusual occurs. It does.

Dr. Floyd is awakened from hibernation early; the Leonov has detected the presence of chlorophyll on the surface of Europa. As the ship passes that small, icy world, the crew sends a probe down to the surface. During its descent, they maneuver it through crevasses and fissures in the thick ice, its instruments probing and analyzing, sending data back to the main ship. The monitor, receiving television images from the probe, sees a flash of green from under the ice. Then, the probe is destroyed in a burst of energy that hurls it back into space. It rockets past the Leonov, shaking it in the wake of its passage. The data which the probe had been collecting is suddenly gone, but the crew witnessed it as it was being processed. There is chlorophyll on the surface of Europa and the potential for life on a planet other than Earth.

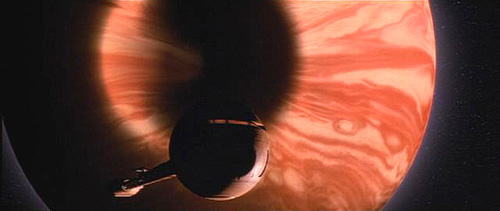

Before the crew can contemplate this discovery or the incredible way the data was lost, they are forced to deal with their rapid approach to Jupiter. To slow their forward speed, the Soviets have opted to use an untested process, aero-braking. The Leonov will achieve orbit and travel into the upper fringes of the Jovian atmosphere by deploying huge inflated bags that will drag on Jupiter’s gasses, slowing the spacecraft. If their maneuvers are not precise, or the calculations are in any way flawed, it could prematurely end their journey. A failure means they will either burn up, slow too greatly and fall to Jupiter’s gravity, or deflect off of the atmosphere and hurl into deep space, sending them beyond the range of their limited fuel and supplies. The ride is bumpy, violently so, and turns the ship into a fireball streaking across the face of the gas giant, but it works.

Settling into a calm orbit, they approach Io and the tumbling Discovery. Discovery is spinning end-for-end. Two crewmen drift towards the Discovery and make a tethered walk “down” the sulfur-encrusted surface of Discovery, against increasing centrifugal forces, to the bulbous command module. Once inside the ship, they stabilize Discovery and survey its status. The vessel still contains sufficient reserve power to bring the systems on line. Curnow begins system repairs while Chandra carefully brings HAL back to life. Chandra erases all memories of the conclusion of the earlier mission but not before extracting the data revealing the reason for the mishap.

Chandra explains to the gathered Americans that HAL had been fed conflicting instructions. He explains that HAL was given all the parameters for investigating the monolith in the event that the crew were killed or incapacitated. He was also instructed to deceive Bowman and Poole about the nature of the mission until they reached Jupiter to prevent them from accidentally revealing the information in their personal transmissions with family and friends. This deception ultimately conflicted with his basic programming, which was to accurately translate and report data as observed and without embellishment. Chandra confronts Floyd, believing that he was responsible for the conflicting orders and the failure of HAL. Floyd recognizes the true source: the instructions were placed into HAL by the National Security Council. Dr. Heywood Floyd is furious.

In the meantime, aboard the Leonov, the Soviets have been studying the monolith in orbit around Io. They develop a plan to have one crewman, Max, pilot the Leonov’s pod along the surface of the monolith, taking instrument readings at close range. The Americans object, especially Curnow who has become friends with Max over the past few days. Despite the objections, the Soviets enact the plan. The pod moves over the monolith, gaining inconclusive readings. Max traverses the length of the monolith but still cannot determine the material it is made of. All signals sent from the pod into the monolith are simply absorbed. While he is taking readings, bursts of energy suddenly run across the surface of the alien device. They engulf the comparatively tiny pod and hurl it across space towards Earth.

In the movie’s first semi-surreal moment, David Bowman’s widow is seated in her kitchen, watching a television report of the deteriorating situation in Honduras and the growing tensions between the US and Soviet Union. The transmission is interrupted, and Dave Bowman appears on the screen. He carries on a conversation with his former wife, wishing her well. The scene shifts to a hospital ward, where David Bowman’s elderly mother is lying in bed. She is comatose and near death. The attending physician leaves the room; the nurse at the station, surrounded by monitors, is reading a magazine, so does not see Mrs. Bowman suddenly sit upright, a sweet smile on her face, or the hairbrush that of its own accord softly brushes her hair. The nurse is jerked to awareness by the alarm from Mrs. Bowman’s monitor; she and the doctor rush in to find Mrs. Bowman has died, a smile on her face, the hairbrush from her nightstand cradled in her hands.

Back in orbit of Jupiter, the political situation has finally impacted the space mission. The astronauts and cosmonauts get simultaneous messages telling that the Latin America conflict has reached crisis proportions. A Soviet warship was sunk by American fire while trying to run the American blockade around Honduras. Diplomatic relations have broken off. The American astronauts are ordered to Discovery, and the Russian cosmonauts to the Leonov. Neither group is allowed aboard the other ship and all communications are forbidden, except in emergencies. They await the launch window which will take them back to Earth with the minimum expenditure of precious fuel. For the Discovery, the window is 28 days away.

As the Americans settle in for a four week wait, HAL contacts Floyd with a message saying that they cannot delay and must leave the orbit of Jupiter in 2 days. Floyd thinks it’s a practical joke by Dr. Curnow but HAL informs him that the mysterious message originated from lost astronaut, Dave Bowman.

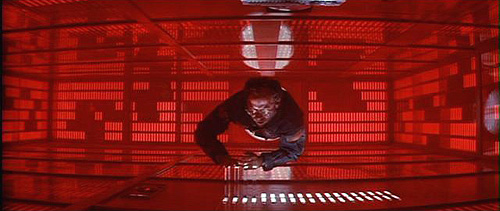

The movie does go into a surreal sequence at this point: Dave Bowman appears to Dr. Floyd. In the pod bay, they have a conversation – Bowman can’t explain what is going to happen beyond “something wonderful” – during which he switches appearance between the young man who went on the mission nine years before, an elderly man, and an ancient man, and ultimately as the infant “star child”. Bowman’s shifting ages duplicate the images of the ending of 2001.

Thoroughly convinced, Floyd violates orders and goes over the Leonov, where he tries to convince his Soviet counterpart they must leave immediately. She is skeptical until the monolith suddenly disappears in the middle of their conversation. Shortly thereafter, a dark spot appears in Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. Strange things are happening around Jupiter and the need to depart is obvious. The Americans and Soviets work feverishly to link the two ships together, intending to use the Discovery as a booster rocket to hurl the Leonov away from Jupiter. The Leonov’s resources will take them the rest of the way home. HAL is programmed to conduct the controlled burn and both crews move aboard the Leonov as things begin to look more bleak on Jupiter.

Dr. Curnow focuses a telescopic camera on the spot, and HAL determines that it is composed of thousands of monoliths. They appear to be replicating inside the Jovian atmosphere.

The Discovery activates its engines and the ships depart. Dr. Chandra informs HAL that he might not survive whatever event may follow their departure. HAL continues to monitor the situation as the Discovery is released by the Leonov, which ignites its own engines, increasing its escape speed. Just then, Jupiter explodes into a fireball, hurling an energy shockwave out in all directions.

As the shockwave races for the Discovery, David Bowman’s voice addresses HAL, instructing him to turn his antenna back towards Earth and send a final message. HAL complies, realizing this is his one last function. He transmits a final message before the shockwave incinerates the Discovery:

ALL THESE WORLDS ARE YOURS

EXCEPT EUROPA.

ATTEMPT NO LANDING THERE.

USE THEM TOGETHER.

USE THEM IN PEACE.

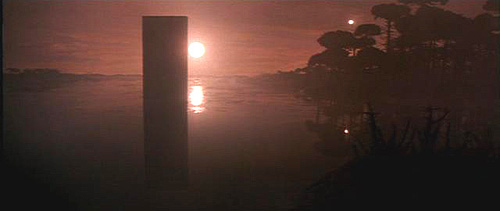

The film ends with a dialog by Floyd describing how mankind was humbled by the appearance of a second sun in the solar system, and how they realized how petty their squabbles over Latin America were in the “big picture”. Both the US and Soviets recalled their war machines and began to work together in peace. In the final sequence, Europa is shown in a distant future. No longer the frozen wasteland of the past, it is a swampland teaming with life. Standing in the middle of the swamp is a monolith, ready to carry on its mission with the next species.

COMMENTS:

2010 is not the same kind of film 2001 was. It was far less surreal, or spiritual, than Kubrick’s original film. The models and effects were excellent, but there did not seem to be the same attention to detail in the filmmaking. While the actors wore red “traction devices” on their tennis shoes, there was no sense that they were weightless while aboard either ship. In 2001, the effort was made to simulate that effect while the actors were moving around. In 2010, cursory efforts were made to show something space-like, but the effect falls far short of the original example. Where 2001 was heavily entrenched in science, 2010 embraces it where convenient but does little to regain the documentary feel of the original film.

Where Kubrick relied heavily on visual and musical cues to tell the story in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Hyams relied instead on expository speeches both in conversations and in the guise of messages to and from home, voiced over external shots of the ships and Jupiter. When compared with 2001, where the spoken word was minimally used, the effect was unfortunate; the viewer had to concentrate on the speech rather than the striking imagery or music. With the exception of the stirring “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” during the title sequence, the soundtrack is eminently forgettable in this film, a far cry from the unforgettable classical soundtrack of 2001.

2010’s true strength lies in the powerful delivery by its actors. They work extremely well together. Roy Schneider’s performance is exceptional, especially when compared to the stiff and wooden portrayal of Dr. Heywood Floyd in 2001. Curnow and Max’s interchanges are entertaining and help the film flow smoothly through the technically based moments. Bob Balaban’s portrayal as Chandra provides a convincing genius, seemingly bordering on the mad scientist level. Representing the Soviet ideals, Helen Mirrin provides a likeable and convincing female commander torn between her sense of duty and her personal feelings thrown further in array by the extraordinary events happening around her.

Where 2001 sacrificed character development in favor of the story, 2010 fully develops each character in a manner that makes you enjoy all of them. There are no villains or adversaries anywhere in this film; all the characters are likable. To some degree, though, this has a negative impact on the storytelling. Its hard to get any sense of tension between the US and the Soviets. In the opening scene, Dana Elcar eliminates any chance of viewing the backdrop story as a Cold War conflict, with competing interests worthy of armed conflict. The dialog is there but it rings hollow since all of the conflicting events are presented as if from newspaper reports involving nameless military forces for a nameless cause. Consequently, when Floyd violates orders and travels to the Leonov, the audience has no real belief that he’ll be arrested or detained.

In fact, the “feel good” sense of the film undermines one of the key points of the storyline. Chandra explains that HAL went psychotic because he was told to lie due to direct orders from the White House. In an obvious political statement, the character declares, “HAL was told to lie by those who find it easy to lie. HAL doesn’t know how”. The moment is supposed to be profound but it fails; you have to wonder what these people expected in the first place.

Earlier in the film, Demitri (Elcar) makes a special point of telling Floyd that it was stupid and foolish for the Americans to keep the monolith hidden instead of opening it up to the world to examine. During the course of the film, several characters are irritated and then angered by the US government taking steps to keep the discovery of highly advanced technology secret from potential enemies. Undoubtedly, none of the characters have ever seen examples of governments taking small technical advancements and turning them into highly lethal weapons, which is quite unlikely, given the high-level experience each of these characters were supposed to have. These considerations lie at a secondary level from the onscreen story but its precisely this level of detail that allows Kubrick’s film to remain so powerful decades later.

Additionally, one of the reasons 2001 is considered the ultimate classic in science fiction is that it delivers pure science fiction without attempting to teach or indoctrinate the viewer. Consequently, the political preaching in 2010 is more obvious.

Still, 2010: The Year We Make Contact is a good film that stands well on its own merits. The effects are good, the story moves at a very good pace, and the the visuals are well suited to play on a large screen TV in widescreen format.

CAST: Roy Scheider (Heywood Floyd), John Lithgow (Dr. Walter Curnow), Helen Mirrin (Tanya Kirbuk), Bob Balaban (Dr. R. Chandra, HAL’s inventor), Keir Dullea (Dave Bowman), Douglas Rain (voice of HAL 9000), Madolyn Smith (Caroline Floyd), Dana Elcar (Dimitri Moisevitch), Taliesin Jaffe (Christopher Floyd), James McEachin (Victor Milson), Mafy Jo Deschanel (Betty Fernandez, Bowman’s wife), Elva Baskin (Maxim Brajlovsky), Savely Kramarov (Dr. Vladimir Rudenko), Oleg Rudnik (Dr. Vasili Orlov), Natasha Shneider (Irina Yakunina), Vladimir Skomarosvsky (Yuri Svetlanov), Victor Steinback (Mikolai Ternovsky), Jan Triska (Alexander Kovalev), Larry Carroll (TV Anchorman), Herta Ware (Jessie Bowman), Cheryl Carter (Nurse), Ron Recasner (Hospital Neurosurgeon), Robert Lesser (Dr. Hirsch), Candace Bergen (credited as Olga Mallsnerd)(voice of SAL 9000). Arthur C. Clarke (Man on Park Bench – uncredited).

– written by John Pickard