“Open the pod bay doors, HAL.”

Considered by many to be the best science fiction film of all time, 2001: A Space Odyssey is frequently on the top of the list of best films of any genre. Four years in the making, this 1968 film was a collaboration between renowned science-fiction (and hard science) writer Arthur C. Clarke and visionary director Stanley Kubrick. Breaking from the established science fiction fare of the time, 2001 painted a very realistic and scientifically accurate portrait of what space travel in the near future was likely to be like. The technologies portrayed throughout the film were scientifically probable and practical. Subsequently, the depictions and images created for the film were realistic and memorable. Nearly all Apollo and Space Shuttle crewmen reference 2001 as accurately portraying the real experience.

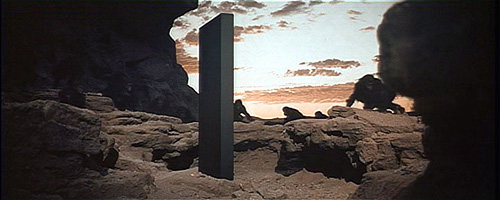

The film is broken into four segments, each depicting an important event representing a step that brings mankind closer to contact with an unseen and somewhat manipulative alien species. It begins in the dim, early time of human history, not long after man’s ancestors came down from the trees and began living in caves. The segment centers on one small tribe of pre-human apes struggling for survival on the African plains. There they scavenge for food and are themselves preyed upon by lethal predators. They react with fear and anger as they encounter a neighboring tribe, “the Others”, at the nearly-dry riverbed. There, conflicting over this life-saving resource, each group noisily defends their side of the pool, neither getting close enough to the other to pose an actual danger. This condition continues until a new object, a black slab, abruptly appears outside of the man-apes caves. Hesitant at first, they gather around the strange device, touching it and reacting to it. As suddenly as it appeared, the monolith disappears and life for the tribe returns to normal.

One of the man-apes, “Moonwatcher”, digs for insects among the skeletal remains of an animal when he grasps an intact leg bone. In an obvious leap of intuition (emphasized by a quick flashback of the monolith), he starts swinging the leg bone among the rest of the skeleton. Smaller bones break into fragments. Inspired, he starts swinging the hard bone as a club, smashing the bones around him to pieces. He quickly applies this new knowledge to a living animal, and shows his tribe the use of this new tool, giving the man-apes the ability to hunt for food. Moonwatcher’s tribe will hunger no more.

Shortly thereafter, the tribe is drinking from the stagnating pool in the drying streambed when “The Others” again appear, screaming defiance. One bold leader musters up his courage and actually crosses the water to challenge Moonwatcher and his companions – and is promptly beaten to death by the superiorly armed and fed tribe. The most ancient ancestors of man have learned the use of tools and the use of warfare. In the most simple way, they have begun the long struggle to the stars.

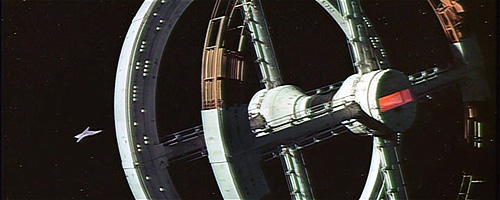

The second segment begins in the year 2001. Dr. Heywood Floyd is the only passenger on a special shuttle flight from Earth to the partially completed orbital space station. He is NASA’s director of operations, ultimately bound for the American moonbase, Clavius. Aboard the station, while awaiting transfer for his flight to the base, he encounters his Soviet counterparts who inquire as to unusual activities at Clavius, rumored to be an epidemic that has crippled the base and may threaten the safety of all space missions if not properly contained. The Soviets are understandably concerned. Floyd is subdued about the rumor, neither confirming or denying its reality.

When Dr. Floyd arrives at Clavius, he conducts a staff briefing during which he reveals the real reason for the cloak of secrecy. A survey team on the moon, investigating a significant magnetic anomaly, has uncovered a rectangular black slab, a few meters high, that had been deliberately buried beneath the moon’s surface more than four million years before. The object represents the first recorded evidence of intelligent life other than man and proves that some intelligent beings existed well before man’s rise to civilization.

Floyd accompanies the survey team to the excavation site, where the monolith has been uncovered. In a duplicate movement, shadowing Moonwatcher’s experience millions of years earlier, Heywood Floyd reaches out and touches the monolith as the sun starts to rise above the horizon. The excavation is bathed in sunlight and the monolith emits an ear-splitting radio shriek as the sun hits it. The alien device has awoken, alerting its creators that mankind has mastered space travel and has left its ancestral home. The radio beam is aimed directly at Jupiter.

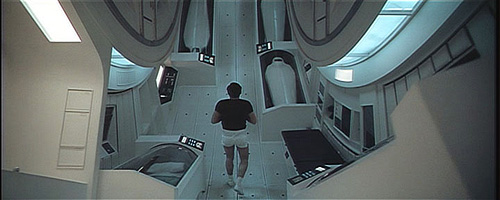

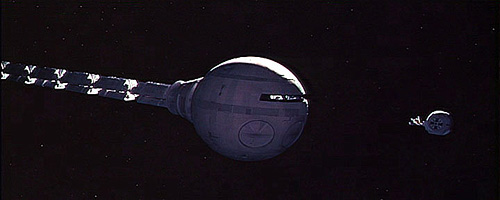

The film’s third segment begins eighteen months later, aboard the spacecraft “Discovery”, en route to Jupiter. Controlled by an automated system monitored by the most advanced computer system yet developed, the HAL 9000, the ship carries a crew of five. This consists of three specialists in hibernation, Mission Commander Dave Bowman and co-pilot Dr. Frank Poole. They consider the vessel crewed by six, referencing the HAL 9000 system as an actual crewman. The HAL 9000 is an amazing piece of technology. HAL is a conscious entity, a true intelligence, programmed with emotional responses so precise that debates rage over whether the HAL 9000 series displays emotions that are real or merely simulated. It is able to interact fully with the crew with the full subtleties of human language and enjoys a perfect record of accuracy. It is the most reliable computer intelligence ever created.

As the days pass, the Borman and Poole follow various activities: exercise, chess, reports, telemetry readings, and relaying video messages, both professional and personal. Through this mundane routine, the audience learns that the three sleeping crewmembers spent several weeks in separate training and were placed in hibernation before the mission was launched. HAL inquires as to the reasons for this and references rumors of an object being found on the moon. He declares that he’s uncomfortable with all of the unusual circumstances surrounding their mission being unable to put it “out of his mind”.

As he discusses this, he announces that he’s just discovered a pending failure in an electronic module in the ship’s antenna. They decide to replace the module prior to failure. Bowman goes EVA in one of the spacecraft’s three exploration pods and makes the switch. Upon his return, he and Poole test the module. They can’t find any indication of the fault the HAL 9000 states he detected. They confer with Mission Control on Earth who thinks it might be a computer error, the first ever error in the HAL 9000. HAL refutes this interpretation and suggests replacing the module until it fails; he’s very confident in his analysis. Mission Control agrees with the plan, finding no immediate problem since contact will only be lost short time if it does fail. Bowman and Poole foresee a larger danger. Realizing that the entire ship is monitored by HAL, they meet in one of the pods, away from any of his microphones. Inside the pod they discuss the potential fallibility displayed by the supposedly infallible computer. They develop a contingency plan. If HAL proves faulty, they’ll need to shut down his higher, “thinking” functions and assume manual control of the Discovery. HAL monitors the discussion, focusing his camera through the pod’s small window. Although HAL can’t listen to them, he has the ability to read their lips!

Unaware that HAL knows of their contingency plan, Poole takes a pod EVA to swap replace the original communications module. When he exits the pod in his spacesuit and begins to make the change, the pod turns on its own and overtakes him. Bowman, observing the antenna on a monitor, looks up just in time to see Poole and the pod tumbling away from the Discovery. Poole’s motions are frantic. His air line has been torn from his helmet. He is desperately trying to reconnect it to his backpack unit.

Bowman leaps to action, rushing to another pod. He ignores all normal procedures, failing to even grab a space helmet or proper life support units, and sets out after his friend and only human companion. Despite his quick action, by the time he gets the pod launched its obvious that he’s no longer on a rescue mission but a recovery operation. He jets from the main ship, catching up to Poole’s body which he gathers in the articulated arms of the pod and returns to Discovery. The HAL 9000 refuses to let Bowman back aboard. He reveals that he knows of Bowman’s and Poole’s plan to disconnect him, flatly stating that their mission is too important to allow such a thing to occur. Concurrently, HAL ceases life support to the sleeping crewman. David Bowman faces a harsh reality. His only remaining access into the ship is to manually open a hatch and crawl through. He’s left the ship without his helmet.

David Bowman uses the pod’s arms to manually open the access hatch into the Discovery and lines up his pod’s hatch with it. He blows open the pod’s hatch with explosive bolts, hurling himself into the airless accessway. Exposing himself to vacuum for a few precious moments, he manages to activate the hallway’s controls and seal the hatch, flooding the passage with air. Before HAL can react further, he dons a helmet and life support pack. Now fully self-contained, he makes his way into the bowels of the ship, where HAL’s circuits were located. Accessing a sealed chamber, he slowly disconnects the circuits that control HAL’s cognitive abilities; HAL’s soft voice tries to dissuade Bowman from his actions, but as his mind fails he reverts to earlier and earlier programming. As the last of his intelligence functions shut down, he sings a song he learned shortly after he had been activated, “Daisy”, as his voice slows, deepens, and finally ceases.

HAL’s last act is to activate a recording. It explains the true nature of the Discovery’s mission, of the finding of the monolith and the fact the radio scream it emitted was directed at Jupiter. Only HAL had known; and HAL had been obliged to keep the true nature of their mission secret from his crewmates.

The final sequence of the film truly sets 2001: A Space Odyssey apart from other films of its time and genre. Highly interpretive, the sequence is presented without any dialog and relies heavily on symbolism that is both bizarre and unexpected. Stanley Kubrick wanted the viewer to create his own interpretation of Bowman’s final journey. The audience is forced to do this as the film does nothing to explain what most of the images mean or even what they are supposed to represent. Many viewers were forced to read the novel to understand the ending of this film.

Discovery has reached Jupiter, and Bowman, now completely alone, finds that in orbit around that giant planet is a monolith hundreds, perhaps thousands of times larger than the one found on the moon. He sets out in one of the two remaining pods – and is somehow transported through lights and sheets of energy, shapes and colors and planes of changing, all of which assault his senses. Novae and Supernovae expand, energies ebb and flow, and his every sense trembles as he tries to absorb it all. Then he is traveling through landscapes of fire and ice, familiar yet totally alien. Light and dark intertwine, primordial flame coexisting with infinite cold.

… and then it stops.

The pod sits in the corner of an elaborate hotel room, all white, furnished in an Elizabethan style, with a rich golden brown comforter on the bed. As Bowman watches through the pod’s window, he sees a space-suited figure standing before him. It is himself. Through a series of looks and transformations, Bowman is taken through increasingly aging forms.

He hears noises, and investigates the bathroom, then realizes there is a figure back in the bedroom, seated, eating, his back to the door where Bowman is standing. The figure rises and turns. Again, it is Bowman, older and graying. When the older Bowman sees no one standing behind him, he returns to his meal, sipping his wine. Taking another bite, he then accidentally knocks the wine glass off of the table. When he bends to retrieve the broken glass, he sees that there is an old man, an ancient man, in the bed. Of course, it is Bowman, who is dying, staring at a monolith that stands at the foot of his bed. Then, on the bed, a sphere of energy appears containing a human infant, eyes wide, staring at the monolith. Bowman has been reborn as a star child.

These shifts in perspective are discomforting, abrupt, and add to the sheer awesomeness of the film’s closing views: the moon, pulling back to reveal the Earth, and pulling back to reveal the star child infant staring at the Earth.

COMMENTS:

The last sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey draws highly contrasting responses from audiences. Some love it, seeing it as revolutionary and a grand attempt to convey the truly alien environment Arthur Clarke envisioned. Others, including many who otherwise absolutely love the film, despise the entire end sequence, seeing it as a bad fit for an otherwise grand film.

Love or hate the ending, the entire film holds up very well decades later, even in an era of computer effects and digital wizardry. If at all possible, this should be considered a must see in a theater, the venue for which it was created. Failing that, it’s a mandatory widescreen view on the largest screen possible with the best sound system available.

The story is told largely through the visual and sound effects created and carefully mastered to keep dialogue to a minimum. When the story focuses on the monolith, choral vocals and discordant harmonies, not easily recognized as human voices, are used to portray the feeling of an alien influence. Throughout the film, the dialog that is used is purposeful and serves to establish the characters, situations, and conflicts. There is excruciating attention to detail, from the Velcro slippers the Pan-Am stewardesses wore to the painstakingly realistic depiction of weightlessness. Throughout the entire film, the fantastic aspects of space travel look routine, an every-day occurrence.

Stanley Kubrick’s musical score was nothing short of brilliant, using only classical, orchestral pieces throughout the film. Probably the most memorable sequence throughout the film is the space shuttles docking maneuvers with the dual wheeled space station, during which Johann Strauss’ “Blue Danube” echoes through space. For many, the “Blue Danube” will forever be linked to this film. Performed by the Berlin Philharmonic, it was used to convey the grace and majesty of space, the dance of weightlessness, the silent movement in the orbit of Earth and beyond. Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” opens the film, the grand, soaring opening notes another immediate link from music to film. Other classical pieces used in the film include Khatchaturian’s “Gayaneh Ballet Suite” (performed by the Leningrad Philharmonic), Lizeti’s “Atmosphere” (Southwest German Radio Orchestra), “Lux Aeterna” (Stutgart Schola Cantorum) and “Requiem” (Bavarian Radio Orchestra).

Kubrick personally designed and directed the effects shots that were supervised by Wally Veevers, Con Pederson, and Douglas Trumbull (Silent Running, Close Encounters of the Third Kind). The spacecraft and moon models were superb, far beyond anything ever seen on the screen at the time. Everything, from the huge space station to the Discovery’s tiny pods, was realistic and practically feasible. Very few “space” films, before or since, have had such realistic special effects. Kubrick wanted to ensure the mastery of his work. Consequently, when 2001 was completed, he had the model of the Discovery destroyed so it couldn’t be used in any other film.

Rick Baker (Star Wars) made such strides in costuming through his work for the man-apes that the film was rejected for consideration for an Academy Award as the reviewers falsely believed he had used real apes for the close-up shots. His techniques significantly altered costume making, especially in the areas of deform masking and surface texturing. Many of his breakthroughs were adapted to bring life to the inhabitants of the Planet of the Apes series.

2001 is, beyond doubt, Kubrick’s best effort at filmmaking. Unlike many science fiction efforts before and since, 2001 looks and feels real, even more than 35 years later.

CAST: Keir Dullea (Dave Bowman), Gary Lockwood (Dr. Frank Poole), William Sylvester (Dr. Haywood R. Floyd), Daniel Richter (Moonwatcher), Leonard Rossiter (Dr. Andrei Smyslov), Margaret Tyzack (Elena), Robert Beatty (Dr. Halvorsen), Sean Sullivan (Dr. Michaels), Douglas Rain (voice of HAL 9000), Frank Miller (Mission Control voice).

– written by John Pickard