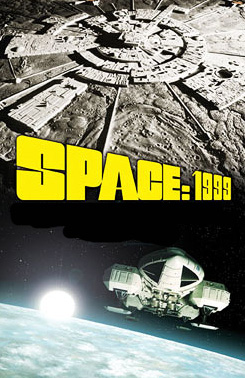

Perhaps the ultimate achievement of British science fiction, Gerry Anderson wowed audiences with his rival to Star Trek, 1975’s Space: 1999. His road to production was difficult. Anderson attempted to get the greenlight to on a second season of his earlier show, UFO. The producers at ITC, in London, were no longer interested in exploring that theme. Initially disappointed, Anderson managed to negotiate an even larger budget for a series. Undaunted by the rejection of UFO, Anderson detailed a scenario in which 19 years had passed and SHADO, the secret organization that fought aliens in UFO, now inhabited an enlarged moonbase, equipped with advanced weaponry for defending mankind. The new concept also involved launching the moon away from Earth to directly encounter alien invaders before they neared the homeworld. Authors Christopher Penfold and Johnny Byrne hacked apart Anderson’s initial concept, originally called “UFO: 1999”, much to the dismay of Gerry and his wife, Sylvia, who always had a close hand in her husband’s projects.

Their revamp was re-titled “Menace in Space.” In this rework, Earth had been destroyed, leaving a stranded moonbase to avenge the millions of dead citizens of the homeworld. ITC rejected the idea believing that American audiences would hate the premise of a destroyed Earth.

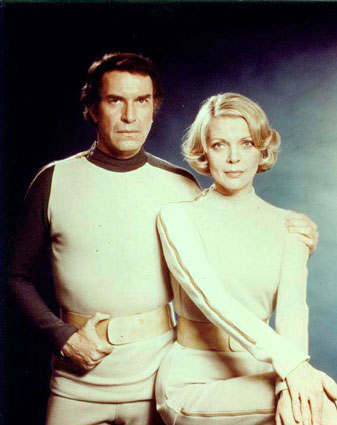

Robert Culp was chosen as the lead. ITC felt that a strong American actor would bring in American audiences, desperately needed to make the show a financial success. Late in negotiations, Robert Culp insisted that he would also direct, a condition that ultimately led to his rejection. Gerry Anderson then turned to husband and wife team Martin Landau and Barbara Bain who assumed the lead roles of Commander John Koenig and Dr. Helena Russell.

|

The moonbase was renamed as Moonbase Alpha, with a second smaller Moonbase Beta on the other side of the moon. Alpha would be the last stand of mankind, or was to be, except the Earth couldn’t be destroyed. This posed a serious problem for Anderson who worried that Moonbase Alpha would be marginalized if mother Earth was always there to save the day. A new script was developed with a new title, “Space Probe”, that was then renamed to “Space Journey 1999.”

Gerry and Sylvia authored an alternate script for the pilot episode entitled “Zero G”, that, in keeping with the agreed format, ran 25 minutes for a half hour presentation. In this storyline, malevolent aliens reduced the Moon’s gravity to zero, thus causing Commander Steve Maddox and the inhabitants of Moon City, to begin their adventures as the moon drifts out of orbit. George Bellack performed a radical rewrite of this script, changing it to a 90 minute film, calling it “The Void Ahead.”

After further review, everyone agreed that neither “Space Journey 1999” or “The Void Ahead” were viable scripts. The two versions were consolidated into yet another script called “Turning Point,” although the series name was still in doubt. Days before the final completion of filming this script, the series was finalized as Space: 1999 with the pilot being called “Breakaway.”

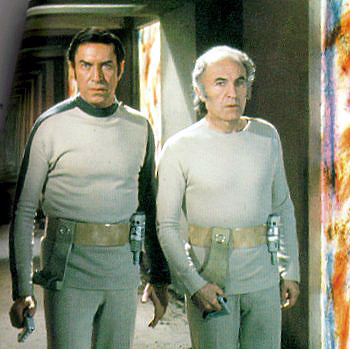

Under the final premise, on 13 Sep 1999, Earth’s moon was blown completely out of orbit by an extensive chain reaction of explosions that spread across the nuclear waste dumps on the moon. Neither Gerry nor Sylvia Anderson were happy with the result. Commander Koneig failed to come across as the strong, silent leader they’d envisioned and Dr. Helena Russell lacked all of Barbara Bain’s real-world personality. Barry Morse played better as Professor Victor Berman. Consequently, through post-production editing, his role was expanded while the lead roles were reduced.

Gerry Anderson gave the production crew a mere two weeks to breath more life into the series. The pilot established the premise but didn’t have characters worth caring about. The authors collaborated and came up with a second episode, “The Siren Planet”, but it was so far out of sync with Breakaway that it had to be dumped. Scriptwriter Johnny Bryne completely revamped “Siren Planet” for a new script that became “A Matter of Life and Death”. This script, and its accompanying notes formed the template for the entire series.

The original concept was to focus almost entirely on the characters of Commander Koneig and Dr. Russell. The new approach focused far more on the secondary characters of Alan Carter, Sandra Benes, Paul Morrow, and Dr. Bob Mathias. Australian actor Nick Tate soon became the dominant feature in the series as the easygoing and most realistic all-around character, Chief Eagle Pilot Captain Alan Carter.

1

His base character was defined in “Breakaway” where he was to have been in charge of a deep space probe to the newly discovered planet Meta, but was drafted to assist in clearing the nuclear waste dumps only to see them explode. Disregarding his own safety, he followed the moon in his Eagle with the intention of helping survivors. As the series developed, he became the hero figure and was used more and more as scripts developed.

Minor characters began to take on more significant roles but never fully blossomed. David Kano, a computer expert with an electronic chip embedded in his skull that allowed him to tap directly into the base’s computer, was planned to be a key team member but fell to the wayside.

The moonbase’s data coordinator was supposed to maintain a key subplot, being that of Alan Carter’s girlfriend who was intent on finding a world where they could settle down and raise a family. This idea was shelved as it never fit in with any of the other story concepts.

Other minor characters that should have appeared in their roles throughout the base were entirely forgotten in some storylines. This became so commonplace that some actors were never called for filming on some episodes. This shifting of screen time upset Martin Landau who threatened legal action with his contract. Barbara Bain likewise relied on an unwritten agreement between her and Gerry and Sylvia Anderson. Other scripts were developed that focused more on the central characters.

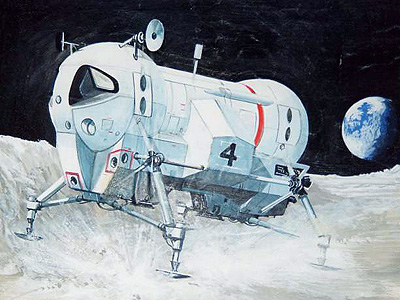

Moonbase Alpha was designed to be a sprawling complex 2.5 miles wide located north of the Sea of Showers in a large crater plateau. Its core was Main Mission located at its center atop a ten storey section. Some portions were 2.5 miles below the lunar surface. The base was completely self-sufficient, generating its own power through a mixture of three nuclear reactors and solar power, capable of supporting a few more than 300 people. Its food was produced via hydroponics, while all water and air was constantly being recycled.

Each episode would start with a pre-credit teaser that built to a dramatic incident, followed by the thoroughly spectacular title sequence. Barry Gray’s theme built slowly as both Landau and Bain were credited, and the Space: 1999 logo appeared against the backdrop of Moonbase Alpha. An Eagle crashed into the moon’s surface and exploded; cue: clips, showing dramatic, action and special effects shots from the upcoming episode raced across the screen broken by captions of “THIS EPISODE” and “SEPTEMBER 13, 1999” (the date when the events of Breakaway took place).

Throughout its run, Space 1999 showed some impressive support actors including Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. Writers like Michael Crichton contributed scripts although the ideas were always heavily edited by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson. Many of the stories ended up being intense negotiations like the inclusion of Keith Wilson’s octopoid monster that haunted the spaceship graveyard in “Dragon’s Domain”.

As the show progress, critics like science fiction author Isaac Asimov slammed the show for its lack of scientific details that went well beyond the flawed basis of having a moon drift through space at below lightspeed and encounter a different solar system each week. Gerry Anderson took great offense to this and often responded that in deep space “anything could happen!” He became increasingly livid with those who constantly compared Space: 1999 to Star Trek.

The series proved to be a gold mine in merchandising, all of which was licensed by ITC Entertainment. The Eagle and Hawk models by Airfix brought in enough dividends to recoup the investment of the entire series. Games, pillow cases, lunch boxes, Viewmaster discs, and the like brought in immeasurable profits, well beyond the show’s 3.25 million pound budget.

Ironically, the show was a ratings failure in England. ITC failed to market it properly and provided it one of the most haphazard schedulings of any television series at the time. It was huge hit in the United States and has remained strong in DVD sales.

– written by Russell Sanders