“The Sleeper Must Awaken”

There are few works in any genre that can honestly be labeled as “Epic.” In film, there was Ben Hur, or Gone with the Wind. In fantasy, Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings certainly ranks high on that list.

In science fiction, it is Frank Herbert’s Dune.

Written in 1965, the novel described the trials of Paul Atriedes, a young noble thrust into a life of hardship on a harsh desert planet by acts of betrayal and political plots. It described family Houses pitted against each other in games of deadly intrigue across the galaxy, possession of entire planets the ultimate goal. It described a vast universe linked – indeed, defined – by a single commodity.

The super futuristic society in which Paul struggled wasn’t one of flaming rockets and robots. It was a concept of massive transports guided by mutated humans who were able to navigate through multiple dimensions due to the properties of that single commodity: a spice drug called melange.

This rare substance could only be produced on one planet, the planet Arrakis, also known as “Dune”. Nor could melange be synthesized in any fashion that retained its unusual physiological and psychic properties. He who controlled the Spice wielded great power; the Emperor was replacing the oppressive Harkonnen regime with the more benign Atreides. All was not as it seemed, however; wheels moved within wheels, and well-planned disaster quickly struck.

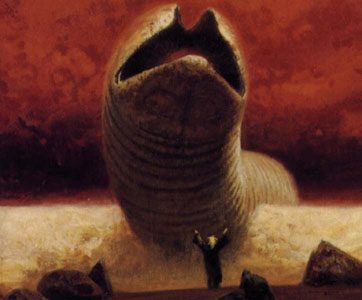

After the murder of his father, Duke Leto, and the betrayal of his household, Paul and his mother flee into the deserts where they join and then lead local tribesmen known as Fremen. These savage warriors prove to have a strange connection to their gods, gargantuan sandworms that roam the deep deserts, and these sandworms prove to be the key to the mystic spice melange. Here, in the forbidden wastes, centuries old prophetic and messianic manipulations come to fruition; but not exactly according to the plans of the manipulators. Finally able to confront his enemies, Paul returns to pit the Fremen’s bravery and strength against the technological superiority of Paul’s enemies, the Harkonnens, and the Emperor who authorized the disbandment of his noble family. In the end, Paul forces a political marriage to the ruler’s daughter, and inherits the throne of the entire galactic empire.

Dune was – and is – renowned for its complexity and completeness in storytelling. Its intrigue wove plots within plots and married political conspiracies to otherworldly fascinations. It was an ambitious book, well beyond the exploits of most science fiction novels. Frank Herbert’s vision paid off well. The novel was a huge success.

In 1969, fans were treated to the first sequel, Dune Messiah, which continued the story of Paul Atreides, now the galactic Emperor, and the challenges he faces in confronting a spectrum of enemies. Like the first novel, the sequel described in detail the breadth of the universe in which Arrakis played a key role. In this tale, all was not well. Paul’s government had become a brutal regime of religious fanatics centered around increasingly powerful faith in his divinity. Fearing being killed and becoming a martyr who would forever seal the worst elements of the new empire, in the end, Paul wanders away to become a desert nomad.

A key element of Dune Messiah was the resurrection of one of Paul’s key servants, Duncan Idaho. This fierce warrior was killed in the original Dune novel and cloned through a mystic process by those who sought to control Paul by promising to return his loved ones who had died in exchange for royal favors. In the end, Paul turns away from them as he does his own fanatical followers.

Frank Herbert completed his original trilogy in 1976 with Children of Dune. This novel, meant to wrap up the saga, detailed the trails of Leto II and Ghanima, Paul’s growing children. Leto II has assumed the throne with the continued absence of Paul, whom most believe to be dead. The ecology of Arrakis has begun to change and much of the population has begun to follow a new mystic character known as the Preacher. Children of Dune introduced few new environments or situations, but closed the story marvelously, with a surprise ending that firmly locked Leto’s rulership by integrating him with the infant sandworms.

The series was so popular that Frank Herbert opted to begin a second trilogy in 1981 with God Emperor of Dune. Continuing the epic thousands of years in the future, this book was remarkable for its portrayal of a continuing conflict between the mutant god and tyrant ruler, Leto II, and a seemingly endless series of cloned Duncan Idahos, all of whom eventually see the ruler as a sinister threat that must be removed. In the end, the Duncan described in this novel wins this battle and succeeds in killing Leto II.

Dune’s 5th book, Heretics of Dune, written in 1984, advanced another 1500 years after the last novel to describe Sheanna, a remarkable young woman who could control the monster Gods of Arrakis, the giant sandworms. She is thrust into interplanetary conflicts and befriended by another Duncan Idaho and Miles Teg, a retired master warrior. Heretics of Dune is primarily an adventure tale and is far less epic than its predecessors. It widens the Dune universe significantly by detailing other locations and settings.

Unknown to most fans, while Frank Herbert continued to write extensive novels, various studio players tried to bring the first novel to the wide screen. Those efforts, which had raged for 12 years with several derailed attempts, finally resulted in the first film version of Dune. This production, released in 1984, was authored and directed by David Lynch, and was a somewhat controversial translation of Frank Herbert’s novel. Produced by Dino De Laurentis and privately endorsed by Frank Herbert himself, this film version only enjoyed a moderate success.

Most who had read the novels felt the film failed to grab the grand story contained in the original novel. Although he was hero of the story, Paul (Kyle MacLachlan) turned out to be the least remarkable element in this film. Kyle’s performance was overshadowed by actors like Patrick Stewart, Max Von Sydow, Linda Hunt, Dean Stockwell, and Sting. Herbert’s messianic themes, that equating the young Atriedes noble as a divine leader of the faithful Fremen, worked poorly on the screen.

In his film, Lynch employed certain unconventional approaches, such as the vocalization of internal thoughts by the majority of the characters, that was difficult for many viewers to accept. The many false starts that had led to this film led to an unsteady application of the talent available to him. For example, the sets built for the film were grand, stunningly so. Many of the costumes were substandard and almost comical. Some designs and certain effects were almost amateurish. Elements, such as the needless gold spaceship for the emperor and the merry-go-round spinning controls for the defender’s weapon’s systems towards the end of the film, further alienated this production from the fierce tale described by Herbert.

Yet, despite these problems, other moments seemed to perfectly seize the atmosphere of the novels. An introductory scene where the emperor (Jose Ferrer) is confronted by a Spice Guild 3rd Stage Navigator remains one of the better scenes of all science fiction film history. The testing of Paul by the Reverend Mother Ramallo (Silvana Mangano), the leader of the Bene Gesserit witch cult, also greatly illustrated the intrigue and feeling from the Frank Herbert’s words.

In the end, Lynch’s film seemed to touch on the atmosphere of the original Dune universe without actually grabbing it. Those unfamiliar with the novels generally enjoyed the film. Those who had read Frank Herbert’s 1965 epic were disappointed.

Yet, in print, the story continued. The following year, in 1985, Frank Herbert released his last Dune novel, ChapterHouse Dune. Herbert continued the tale after the destruction of the desert planet, Arrakis. The book sweeps away the foundations of the earlier novels to explain how the Bene Gesserit witch cult has colonized a green world to turn it into a desert, mile by scorched mile. This story is a bit darker than the already dim outlook of the previous books. Like Heretics of Dune, it is largely another adventure story that ends with a ray of the future.

That future has never been continued. Frank Herbert died on 11 Feb 1986 and it seems the future of Dune died with him.

The future ceased, but not its past. In 1999, working from notes left by his father, Brian Herbert teamed with best-selling novelist Kevin J. Anderson to author House Atreides, the first book in a prequel series. Set 40 years before the original, it told of the mysteries left untouched by the Dune novel. The book centered largely on Paul’s father, Leto and the future galactic emperor, Shaddam IV. As a science fiction tale, it wasn’t bad. Yet, for most fans, it failed to capture the feeling of Frank Herbert’s writing. The book was still a success. Fans were desperate enough for any expansion of the Dune universe to overlook the flaws and changed atmosphere of Brian Herbert’s prequels.

In 2000, Herbert and Anderson released the second prequel, House Harkonnen. In this tale, Shaddam IV became the ruler of the known universe where he is pitted against the ambitious Baron Vladimir Harkonnen. This book weaves the foundations for most of the players in the original Dune. Like House Atreides, it fails to grab the sense of Frank Herbert’s storytelling.

With the waning success of the prequel books, the universe of Dune seemed to be a property no studio wanted to tackle. Several ambitious directors sought to rework the property further but most realized that David Lynch had tried to tackle a story far larger than any single movie could handle, few studio executives wanted to attempt the task or risk any financial investment.

This changed in 2000, when John Harrison, working in conjunction with the Sci-Fi Channel, released a five-hour, made for cable remake of the original Dune novel. This newer film sidestepped some of the studio problems by exercising the television rights rather than attempting another theatrical film. The miniseries format still suffered many of the flaws that had damaged the Lynch version. Some of the costumes were downright silly and special effects, heavily reliant on computer animation techniques, varied from impressive to barely acceptable.

Five hours proved to be an adequate timeframe to relate the large story told in the Herbert’s novel. It also proved long enough to slow down the story considerably and remind everyone what a thick book the movie was based upon. The cast was far less impressive than the previous attempt and the sets were actually substandard to the 1984 film. Plus, in important ways, Harrison ventured even further from the base story than Lynch had done. In all, Dune fans were left feeling that the film version had missed the mark for the second time.

Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson followed the new Dune miniseries with House Corino, released in 2001. In this last prequel novel, Shaddam IV attempted to secure his power by developing an alternative to the spice melange. His attempt to escape the control of the Spice Guild and open up the constraints of space travel were opposed by Duke Leto, who was himself threatened by the militaristic Baron Harkonnen. The novel set the stage for the conflicts in the 1965 book.

John Harrison penned the sequel script for the 2002 “Children of Dune”, a six-hour sequel that encompassed the stories of both Dune Messiah and Children of Dune. The production was less successful than his first miniseries. Some believed this was due to the Dune property being overworked even though Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson enjoyed moderate but steady sales of their prequel novels. Others attributed the weak response to the basic content of the initial stories. Like the novels on which they were based, the Children of Dune miniseries was a dark commentary on the dangers of revolutions and religious fundamentalists. For many Americans, following so closely to the attacks of 9-11, this aspect of the story may have hit far too close to home.

Later in 2002, the universe of Dune experienced an unexpected surge when Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson initiated a new prequel book series. The Butlerian Jihad raced to the bestseller’s list. Set 10,000 years prior to House Atreides, the book describes the events that drove the masses to turn against advanced machines. Planetary empires still possess traces of their Earthly origins but they are already firmly formed into governing Houses. The story is epic, describing the beginning of a century long conflict that long changed the nature of the forming galactic empire.

Herbert and Anderson continued their second trilogy in 2003 with The Machine Crusade. Describing the increasing influence of “thinking machines” and the dangers they pose, this novel continues to encompass a wider vision of galactic import. As with all of the prequel novels, the story lacks the depth of Frank Herbert’s writing but it does provide significant background to the original novels.

The last book in this trilogy, The Battle of Corrin, should be released later this year.

Frank Herbert authored his vision when Americans were largely ignorant of Arabic traditions and the ways of the Middle East. When Dune was printed, Arabs were generally seen as friendly towards the western world and their culture was exotic and intriguing. Frank Herbert’s hero, Paul Atreides, a man kicked from his nobility to lead waves of religious fundamentalists against the established governments, now stands far too closely to terrorist leaders like Osama Bin Laden for many to enjoy this story as they once did. Further hampering its success, the detailed world of Dune has been overtly portrayed by George Lucas as the desert home of Luke Skywalker, Tatooine. Lucas even lifted the God Emperor version of Leto Atreides as the template for his Jabba the Hutt. Some enjoy the expansions of the prequel books. For many others, the magic of Dune has withered and might never return.

For some, the sleeper has yet to fully awaken.

– written by the Two-Brained Cylon